I find Christian faith coherent, intellectually rigorous, and deeply soul-satisfying.

Why?

Probably because I have been fed a hearty diet of Reformed Theology.

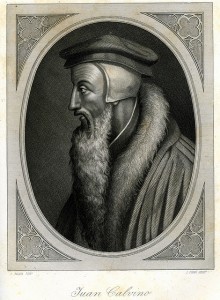

- I did my doctoral dissertation on John Calvin, the Reformed theologian who shaped the tradition more than any other.

- For a good long while I’ve regularly taught the theological summaries that make up the Presbyterian theological standards, the Book of Confessions, to church members and seminarians.

- I’ve written a small book, to help groups study one particular Reformed confession, the Heidelberg Catechism, as well as a growing number of blog posts on the topic.

Here’s how it works

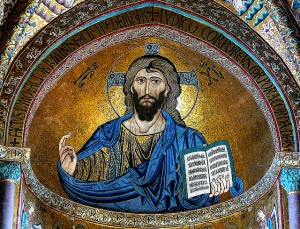

Reformed Theology starts from an encounter with Jesus Christ that prompts a search to understand the whole of the Bible.

Reformed Theology is always an exploration of what God has revealed in Scripture. But when it is doing its job it is deeply rooted in the joys and sorrows of the human condition. And whether it is front and center or behind the scenes, this exploration is always in conversation with the best Christian theologians from across the ages.

That is what I want to point out about Question 18:

18 Q. Then who is this mediator —

true God and at the same time a true and righteous human?

A. Our Lord Jesus Christ, who was given to us to completely deliver us and make us right with God.

It is coherent

If you rip it out of its context, as I’ve just done, you can see it makes clear and precise assertions: Jesus is the mediator (between God and humanity, as I assume you know). He is uniquely able to take that role because he is connected to both sides: he is truly God and he is truly human; enthroned in heaven, and standing among us on earth. He delivers us, or frees us from an unnamed problem, and fixes something that was broken between humanity and God.

It is biblical

Every bit of this can be linked to Scripture, and the footnotes will take you there. They cite Mathew 1:23 where Jesus, born of Mary, is called “God with us,” and 1 Corinthians 1:30 where Jesus is described as our “righteousness and sanctification and redemption.” They cited two other passages and could have cited many more. Q18 is actually the conclusion of a discussion, so these points have already been explained with copious biblical citations.

It connects to great theologians of the past

What you can’t see on the surface here is that the Catechism is affirming points that the best Christian theologians have been making for centuries. Points like these were made in the early Church by St. Athanasius (c. 297-373). Much later they were made influentially for the West by St. Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033-1109). It is Anselm, the great Catholic theologian, whose points the Catechism strongly echoes and affirms.

This is Protestant theology, but it is not anti-Catholic (at least not in THIS section!). The writers are affirming foundational points that define Christianity across all boundaries and divisions.

It connects with human need

To see how this little snipped of the Catechism is touching on core human needs, you really have to read it in context.

1. The opening questions lay out the promised goal: we can belong to God through Jesus Christ.

2. The first main section briefly and succinctly (at only nine question it is the shortest part of the document) lays out the problem all of us face: even if we know the kind of life God created us for, we can’t bring ourselves to live it. In fact, when we look closely at our motives, we regularly make choices that take us far away from God. The consequence: our lives are broken and aimed at destruction.

3. Then, piece by piece, in questions 12 -17, the Catechism explores how Jesus Christ generously and completely comes to solve these problems.

Actually the Catechism does a pretty amazing job of making sense of Biblical Christianity.

Interested in an interactive online course introducing Reformed theology? I will be teaching one starting September 2. Short video lectures and great discussion forums will take us through all the core topics, using the documents in the Presbyterian Book of Confessions — including the Heidelberg Catechism of course! It is part of the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary’s “Christian Leadership Program”, a theological education program that has helped equip hundreds for more effective discipleship and service. Click here and scroll down for information!

Thank you for your post. My lack of experience with Reformed theology leads me to ask a question about one of the premises that allows for your observations. You stated, “Reformed Theology is always an exploration of what God has revealed in Scripture.” From an Eastern Orthodox perspective, the revelation of God was through the Word; however, contrary to some Protestants, the Word of God is not the Bible, but Jesus Christ. That is to say, the revelation is the Incarnation, the person of Jesus Christ, who is the Word of God. Therefore, scripture isn’t a revelation as much as it’s a proclamation of a revelation – the kerygma. I guess, to use words from your quote, I might say scripture doesn’t ‘reveal’ anything, as much as it ‘reports’ what has been revealed. It thus follows, for me at least, that if the Bible is a part of the proclamation – instead of the proclamation itself – it must be a part of a larger context (dare I say, tradition?). The Eastern Orthodox Church has a rich tradition for this context, but I wonder, what guideline would Reformed theologians have to discern the proclamation of the revelation as found in scripture? What guidelines would Reformed theologians have to engage the proclamation of the Word through the theology of other theologians? To relate it to your post, how does one put it back in context to connect to great theologians of the past?

P.S. I realize that my comment is very nuanced. Nonetheless, if may spark some interesting conversation.

Thanks for starting the conversation, Fr. Dustin.

Yes, your comment may be more nuanced than I can respond to on the first day of student orientation at the seminary!

Let me start by saying that for Reformed theologians, at least at their best, the Word of God, which is Jesus, is the revelation of God.

It is, however, common to speak of Holy Scripture as “the Word of God”. Sometimes in Protestantism this is stated too flatly; it can sound like the Bible itself is divine — and in some circles it does sound like people are invited into a new relationship with the Bible rather than a living relationship with the God!

There are at least two good reasons for such usage (at least two that I can type a few words on in a few minutes — for a thorough treatment of the topic, Karl Barth is ‘da man. Church Dogmatics v. 1 will explore it in excruciating detail and subtlety…)

1. New Testament usage of the phrase “word of God” is not univocal. Sometimes it is referring to the eternal Logos. Sometimes it is referring to the gospel message. Sometimes it is referring to things spoken by Jesus. Sometimes it is referring to the contents of the OT. One can bend many of these texts to a single meaning, but it takes some work and the plain intended meaning can be lost.

2. The Scriptures hold a privileged place as the record of the life and work of Christ, the Word, the witness beyond parallel to God’s revelation. At the minimum, to paraphrase Paul on the topic, the Scriptures are breathed in by the Spirit and are useful. But classic Reformed theology does a good job, I believe, of articulating that which they saw as lost in the West in their time, but which had been the accepted and orthodox approach to Scripture: Christ is its subject matter, its target or “scopus.” From Genesis to Revelation the whole book is there to point us to Jesus Christ the Word.

As to the second question of the guidelines of Reformed theologians (I speak in the past, of 16th and 17th century writers) as they interpreted Scripture, that is a much bigger topic. A short answer is that they brought

1. a Renaissance understanding that their own minds mattered, as they brought good tools to textual, literary, historical analysis to the work of interpretation and frankly

2. a Catholic understanding that the Tradition mattered, and the best voices of Patristic and Medieval interpretation had to be weight heavily. For Calvin, for instance, John Chrysostom was a much admired guide.

3. So… because the interpretation and use of Scripture for faith and preaching and theology were all front and center in the controversy with Rome, Protestant leaders Reformed and Lutheran developed clear and insightful understandings of the processes and rules and principles of biblical interpretation that were mostly not original to them but drawn from the Tradition of the Church.

I may revisit the question after thought, but have to go for now!

Thank you for your response, despite having a busy day. I enjoy dialoguing.

I completely agree with your first response regarding the “Word.” We have to articulate what we mean by various words (pun intended) very carefully by properly defining them. In this regard, though we both believe that scripture is divinely inspired, we still admit that it’s a collection of various voices that are using words differently, and stressing different aspects of the gospel proclamation.

Your response regarding guidelines in order to speak to other theologians is well written. There may be more to it, however; for example, Henri De Lubac, in his book “History and Spirit: The Understanding of Scripture According to Origen,” makes a sly argument that Scholasticism has led theology astray, because Scholasticism, in his view, leads one to read Scripture (and the Fathers) in such a way that meaning is altered from their original intent. His work, of course, is part of trend that led to Vatican II and a revival in Patristic studies. Frances Young, in her book “Biblical Exegesis and the Formation of Christian Culture,” shows just how differently the Church Fathers approached the text, and how this leads to a different exegesis and hermeneutics than modern methods. This is why the homilies of the Fathers, in her argument, sound, and are structured differently than our modern homilies. Perhaps this long paragraph – my apologies – is to say that while it’s true the Reformers were reading the Church Fathers and engaging Tradition, they ‘way’ they read them may be crucial because it would affect their understanding of the text, or how a text is applied to systematic theology. Of course, the ‘way’ they read them is being affected by that Renaissance mind you mentioned.

None of this is to say that’s good or bad. After all, scholarship is about being in dialogue also with past theologians and their work. I’m simply acknowledging the potential difficulty in determining a canon by which we call discern classical, or traditional, Christianity, especially as methods evolve – food for thought.

Dr. Hansen, your blog lines are wonderful for those seeking more knowledge about the reformed faith. Thank you. I also enjoy reading the dialogue between you and others. I can see I’ve much to learn about other ways that different cultures view our reformed theology idea.