When I read classical Reformed theology, some parts grate on my ears. These challenging bits teach me about myself: they show me where my assumptions about life, the world, even faith, are influenced by the culture I’m steeped in. I too need to learn “Christianity” as a second language.

This definitely happens at Question 12 of the Heidelberg Catechism. Here it is:

12 Q. According to God’s righteous judgment we deserve punishment both now and in eternity: how then can we escape this punishment and return to God’s favor?

A. God requires that his justice be satisfied. Therefore the claims of this justice must be paid in full, either by ourselves or by another.

Ouch.

Eternal punishment and satisfying God’s justice are ideas that send a lot of people running from historical Christianity.

But as a historian I can tell you, this question, probably more than any other, expresses the existential situation of Christians back in the 16th century, both Protestant and Catholic. It reflects convictions about the nature of humanity’s relationship to God that had been prominent since St. Anselm (c. 1033 – 1109): God is the judge, and we are accused criminals in his courtroom. And God is not just any judge, but a kind of royal judge who is court of final appeal. We stand before the King of Kings who personally wrote the laws we are accused of breaking.

I think the hardest thing for post-moderns to swallow is the phrase “we deserve punishment.” Our sense of ourselves and our world is more deeply shaped by psychology than theology — Freud has won, at least for the present.

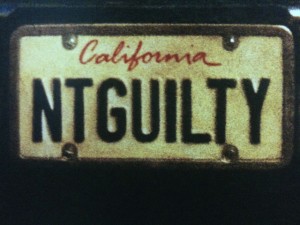

Pop psychology tells us that we feel guilty.

The Catechism is telling us that we are guilty.

If guilt is just a feeling, a problematic feeling, a crippling illusion, we can solve it by finding a different way to feel. Sometimes that is exactly right. Many of us know what it is to be plagued by irrational guilty feelings.

The Catechism is not talking about the illusion of guilt.

I suspect the writers would say we are plagued by the illusion of innocence.

Take as an example the character in the song “Everybody Knows” by the brilliant Leonard Cohen:

Everybody knows that you’ve been faithful

Ah give or take a night or two

Everybody knows you’ve been discreet

But there were so many people you just had to meet

Without your clothes

And everybody knows.

The culture at large agrees that sexual infidelity is not an important matter. The person in the song feels fine — mostly faithful, most of the time. Not a cause for alarm. Certainly not something to feel guilty about. Life goes on.

The Catechism is about a different reality where some guilt is not an illusion; where this child of the “sexual revolution” wakes up before God’s tribunal to find that the Ten Commandments, including that one about adultery, have been the law of the land all along — and breaking them is a capital offense.

That’s the hard part for people today to reckon with.

But if we can at least suspend disbelief on the issue of deserving punishment, we may find that the issue is vastly outweighed in the Catechism by God’s gracious solution.

Question 12 is really about solving the problem: “…how then can we escape this punishment and return to God’s favor?” The answer ends with the tantalizing suggestion that this problem just might be solved by “another.”

And the next 73 questions explain who the “other” is, and revel in the loving, generous efforts of God to deliver us through Jesus Christ.

————

I’d love to hear from you in the comments:

How do you tell the difference between “real guilt” and “guilty feelings”?

(And what’s your favorite Leonard Cohen song?)

First, I find the classic view of inherited sin guilt is difficult for people because individuals/groups are not punished in our society for any kind of inherited guilt (thankfully!) and so it makes God appear unjust in his accusation or punishment. Second, I think people have a tendency to think in terms of “relative guilt.” For example, I have not found a great number of people who are unable to see the fault in their actions regarding a situation that involves harm to another party, but they have fear of being seen as the “primarily” guilty party. “I see my part, but don’t forget about *their part.” In my experience, it seems important that we find ways to speak about the universality of sin in order to address the second concern, but in a way that more effectively addresses what appears to be the unjust nature of God from the first concern.

Thanks, Scott, you thoughtful soul. Always good to hear from you.

(Do you have a favorite Leonard Cohen song, by the way?)

Favorite Cohen song…. maybe… “If It Be Your Will.”

The great thing: that is his favorite too.

Dr. Hansen, in reading this today, I’m just happily grateful that God does not punish me as I deserve, but rather provides a way for me to come to him in eternity!

Amen!