In this series I have pointed out a bunch of key differences between worship in the Protestant West and in the Orthodox East — architecture, candles, icons, processions and so on.

I fear, though, that even with all these things in mind, many Protestants will have a hard time on a first visit to an Orthodox Liturgy. The differences sort of pile up, leaving a visitor with an acute awareness of being a fish out of water.

Is there some big difference tying all these specifics together?

Well, I’m glad you asked. Yes there is.

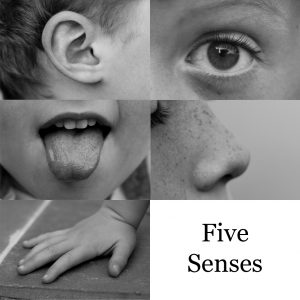

Hearing vs Multi-Sensory

When you add up all the little differences you get one huge contrast:

- In the West we worship with our ears and our minds.

- In the East they worship with all their senses, in the full range of human experience.

Take in what is going on around you in the Liturgy:

Hearing

There is plenty to hear.

- The Word will be read and preached, of course, and that will be familiar.

- But if you listen to the prayers you will be led to call out to God for all the things Scripture says to pray about.

- And if you listen to the hymns you’ll be led to meditate on passages of Scripture, on the wonder of Christ’s resurrection, and on other theologically powerful themes.

But it doesn’t stop at hearing. There is more to take in.

Seeing

There is a vast amount to see, and it is all intended to convey the meaning of the biblical faith.

- You look at the icons and see the key people of salvation history, the scenes of biblical history, the men and women who have lived that faith particularly well through the centuries.

- And as I said in the previous post, you look at the dramatic action, the enactment of Christ coming to you in Word and Sacrament.

Smelling

Which leads us to the sense of smell.

In an Orthodox Liturgy, or any other Orthodox service, as you see the deacon or priest with the incense burner, you smell the complex scent of the incense.

Your nose enters actively into worship. And since you know that the incense is a biblical image of your prayers ascending to God, your nose is leading you to deeper understanding of the faith.

Tasting

If you were Orthodox, your sense of taste would be actively involved in the Liturgy when you receive Communion.

As a non-Orthodox you might see a brief notice in the bulletin saying you can’t receive the sacrament and feel like this is the one sense that got left out. Unfortunately, this message may be the only clear one you receive as a visitor — though really, they are truly glad you are there.

You may still find your taste buds engaged when people come back from Communion. Someone just might hand you a little cube of bread. Go ahead. Eat it.

This is the “antidoron,” meaning “instead of the gifts.” It is part of a larger loaf from which the bread used in the sacrament was removed. The antidoron is blessed and given out to others in attendance.

Giving the antidoron to visitors is not a universal practice, so I hope you won’t feel too bad if it doesn’t happen.

But in some parishes it is a moving gesture of hospitality. They want you to share God’s blessing.

Touching

Orthodox worshippers find their sense of touch engaged in many ways in the course of the Liturgy.

Most prominently you spend long periods standing. In very traditional parishes you won’t even find pews except along the perimeter of the nave.

It’s a respect thing. Who are we to sit in the presence of the King of Kings?

This is “touch” in a different sense than reaching out your hand to something. You feel it in your body when you stand before God for an hour or more.

And there is a great deal more bodily action to be felt.

- As discussed earlier in the series, they will pick up, light, and place candles, make the sign of the cross, and kiss icons before even entering the nave.

- When the Great Entrance is taking place you may see people reaching out to touch the priest’s vestments, like the woman who sought healing by touching Christ’s hem.

- At the end they will line up to kiss a cross held by the priest.

- During the service you may see the faithful bow, kneel, or make prostrations touching their foreheads to the floor.

Especially in a Lenten service with many prostrations, you may well leave worship physically tired.

Why Is Protestant Worship Mostly about Hearing?

So the Orthodox worship with their entire bodies. Protestants tend to mostly listen.

Of course it isn’t an absolute difference. You can probably point to times in Protestant services that drew you to participate in both physical and emotional ways. To say it is all ears and minds is potentially misleading.

But there are strong historical reasons for what I’m saying. Let me explain.

Think back to the origins of Protestantism. Imagine yourself in the early 16th century, when Christianity in the West was all Catholicism. Medieval Catholic worship was primarily a visual experience. And I’m not talking about the pictures and statues.

When they went to a Sunday service, medievals called it “going to see Mass.”

That’s because all the words of the service were in Latin, and you probably spoke English, or German, or French, or whatever. You would sit there and pray, maybe using a devotional book if you were literate and rich.

Then, when the priest said the words consecrating the bread and wine, a bell was rung. You heard that bell and looked up to see him lifting up the elements, now understood to have become the very body and blood of Jesus. You looked, and worshipped, because you were gazing on your Lord.

The Protestants thought this was really problematic. Worshipping something you see, they thought, is dangerously close to idolatry.

And going to a worship service in a language you didn’t understand seemed like a missed opportunity. People needed to hear the Scriptures read, hear the Scriptures explained, interpreted, applied, in a sermon. That way they could better understand, believe, and respond to the call of God.

They thought worship should be about hearing. That’s why the central architectural object was the pulpit. Before amplification, having the preacher high and central was the way to let the Word be heard.

Five centuries later, Protestant worship is still focused on what we hear with our ears, and especially with what hearing leads us to understand with our minds.

Our services can be a bit didactic, a bit talky, a bit cerebral — but hey, we like it that way. We are drawn to engage with the contents of Scripture, learn more, understand better, respond more thoroughly.

Why is Orthodox Worship Multi-Sensory?

We tend to think hearing the Word is so important that we forget that Scripture describes worship in whole-person terms.

Yes, the ears are crucial:

…how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone to proclaim him?” Romans 10.14, NRSV.

But Isaiah found he needed to use his eyes as well — and notice that what his eyes saw was God, and the building, and the furnishings:

In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord sitting on a throne, high and lofty; and the hem of his robe filled the temple.” Isaiah 6:1, NRSV.

If you keep reading in Isaiah, his physical feeling, even a painful feeling, was part of the worship process:

Then one of the seraphs flew to me, holding a live coal that had been taken from the altar with a pair of tongs. The seraph touched my mouth with it … And I said, ‘Here am I; send me!’” Isaiah 6:6-8, NRSV.

And of course there is the special place of the sense of smell, the incense in the Old Testament:

Aaron shall offer fragrant incense on it; every morning when he dresses the lamps he shall offer it…” Exodus 30.7 NRSV.

And as I’ve mentioned, the fragrance the New Testament teaches about in heaven itself, with all falling down in worship carrying

… golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints.” Revelation 5:8 NRSV.

Then there is the sense of taste which can be a metaphor, as in

O taste and see that the Lord is good” Psalm 34.8, NRSV.

But taste, as part of eating, is a required part of New Testament worship by Jesus’ own command passed on to us by the Apostle Paul:

For I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, ‘This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way he took the cup also, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.’ ” 1 Corinthians 11:23-25.

There is a vast amount of Scripture one could mine about the use of the senses in proper worship — starting with the vivid descriptions of what God commanded for tabernacle and temple furnishings.

Think of that whole-person worship it as obedience to the great command:

…you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.” Mark 12.30, NRSV

Or maybe better, think of it as an application of Paul’s instruction:

I appeal to you therefore, brothers and sisters, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship.” Romans 12:1, NRSV

To Paul, “spiritual worship,” or as other translations have it, “reasonable” or “intelligent” worship, is a matter of the body.

After a while our our emphasis on what we hear and think can seem a little narrow.

So when all this multi-sensory stuff is going on in an Orthodox liturgy, think of it as an invitation to bring God every part of who you are.

++++++++++++

This post is part of a series. To start reading from the beginning click here. To continue to the conclusion click here.

I’d love to send each new article, plus announcements of new projects and publications, straight to your inbox. Just scroll down to the black box with the orange button and sign up for my weekly(ish) newsletter, and all this will be yours…

I find the concept of the antidoron interesting. The few times I have been at a RC service I have decided not to go forward for a blessing during the eucharist. I believe if I am not welcomed at the table, I dont want to be blessed by the priest. (May be a pride issue with me.) However, I find the concept of the antidoron to be something to consider.

The offering of the antidoron to a non- orthodox worshipper as one is coming back from the elements does sound more welcoming. It is a way that welcomes a guest without making a point the worshipper is an outsider. On the other hand the RC practice of inviting the outsider to come forward for a blessing results in everyone knowing, oh he/she is not one of us.

Thanks Steven–

I think your reaction is not unusual at all. Open communion between denominations is so nearly universal among Protestants that we really feel the exclusion. Open communion is, really, the only sign of unity shared by the thousands of Protestant denominations. Whereas Catholics are smething like a third of the world’s Christians. They have all kinds of unity amongst themselves, and they are aware that the Protestants rejected them, calling their sacraments false, centuries ago. Exclusion from the Eucharist makes perfect sense to them, but either rankles against our assertion of real but hidden unity in Christ, or dredges up old divisions, arguments, and wounds.

Visiting an Orthodox Church one knows one is in a foreign land, and for some the sense of exclusion is lessened. (We wouldn’t actually know what to do if we did go up!) when someone brings me the antidoron I feel deeply blessed, noticed, welcomed.

But one cannot count on it. Some Orthodox adamantly say the antidoron is only for the Orthodox. And they might be too shy, or not have noticed you, or whatever. Much as in a Presbyterian church it is possible to lay low and not be noticed, or for members of a congregation to not be skilled at hospitality.