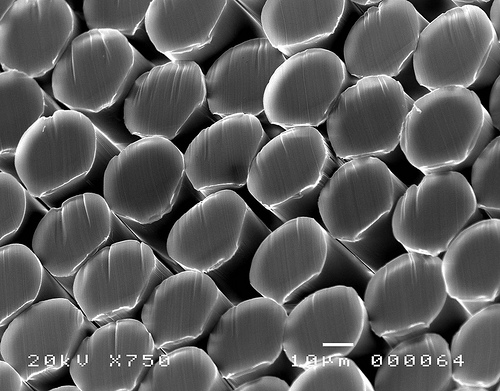

In college I had a lab job doing darkroom work, developing photographs taken by microscopes. The most fascinating were taken through electron microscopes — they revealed the inner structures you could never see from the surface. What looks into our faith like an electron microscope?

“Tell me how it stands with your Christology,” says Karl Barth in Dogmatics in Outline, “and I shall tell you who you are.” Get a good clear picture of this hidden thing, my understanding of the person and work of Christ, and maybe my whole faith is revealed.

The way we think (and believe and feel and know) about who Jesus is, and about what Jesus does, shapes all the rest of our Christian believing and living. On the one hand this strikes me as intuitively obvious. On the other hand I find it is not so easy to explain clearly and coherently.

This week I was trying to make the inner connections explicit for a group of students (who will, in turn, need to do the same for me in writing). I found myself looking to the documents in which the churches have taught the faith to generations: confessions and catechisms. My sampling was limited (Reformed, Lutheran, and Catholic) but fascinating — to me at least. Don’t know how gripping it was for the students.

The were striking commonalities in the main points: All agree that Jesus Christ is truly God, the incarnation of the eternal Son of God, the Second Person of the Trinity. All agree that Jesus Christ is truly human, born of the virgin Mary to live and die a human life.

There were also surprising twists on common polemics and stereotypes: Jesus was born of the “ever virgin Mary” — said the Reformed 2nd Helvetic Confession. “Christ’s death is the unique and definitive sacrifice” — says the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

But what is really important to my way of thinking is the way each document connects this divine and human Person to various aspects of his saving work.

- Thinking about Christ as truly divine brings him to the very beginning of the story as the agent of creation.

- Thinking about him as truly human we find him identifying with us and suffering for us.

- Thinking about him as truly divine AND truly human we find him reconciling us to God in his own self.

- Going to the cross we find this divine-human Christ taking on himself our greatest problems, whether the law or the curse due to sin.

- On that cross we find him saving us in the climax of a great drama, whether it is in terms of satisfying justice or victory over the enemies of sin death and the devil.

- Seeing his whole life as the revelation of God’s nature and God’s will we find him our model, central to daily living of the Christian life.

And we find our assurance and hope in him because in baptism and faith we are united to him — we find salvation does not depend on our goodness, but on the fact that we belong to Christ. We are chosen in him, as the confessions say. Because we are in him we know we are chosen for life.

That is not very systematic. But it does show me that the Church’s teaching about the person of Christ, his identity as divine and human, is the lens through which a whole lot of other teachings have deeper richer meaning.

- When you think about “who Jesus is”, how does it connect in your thinking with “what Jesus does”?

- How does it matter to your personal faith that Jesus is “truly God” — or “truly human”?

I have to admit that my thinking in this area has never been too deep – I have always “simply” accepted that Jesus is fully man and fully God. Then I read about the history around the Council of Chalcedon recently and realized how difficult of a concept this really can be. Learning about the varying opinions at the time on the relationship between Jesus’ natures gave me a much deeper appreciation for the topic. I was especially interested to learn that there were church splits over the result of the council that persist to this day! Fascinating. 🙂

Natasha, thanks for sharing these thoughts. As you found the issues in the great Ecumenical Councils are often pretty challenging. Part of the challenge is the abstract philosophical points involved, but some of it is more about how different our own ways of thinking are from theirs.

It seems when I listen to people talk about their faith that in completely different ways from the Councils, many tend to focus on either Jesus’ humanity OR his divinity, finding help in one side of this and often not really thinking about the other. I could be wrong of course, but it sounds like that at times.