Martin Luther wrote on the Lord’s Prayer. A lot — it was his favorite guide to a richer prayer life, as I recently wrote in a guest post on Anita Mathias’ blog, and as I spent a chapter exploring in my book, Kneeling with Giants. But there is one line of the prayer he never commented on, at least in the texts I’ve found. In your King James Bible it is Matthew 6:13b,

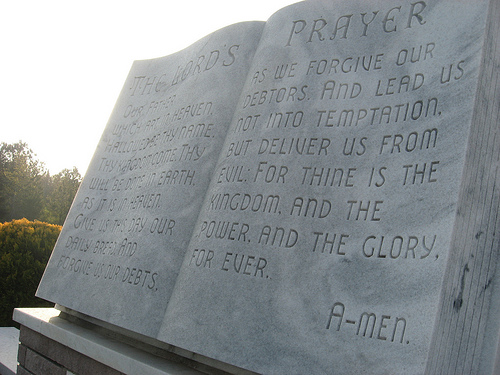

“For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever.”

Unlike Luther, the Heidelberg Catechism discusses this line in Question 128.

I find this fascinating.

Of course there are certain things that are totally interesting to me that most of you might find just a teensy weensy bit boring. A lot of them have to do with the details of 16th century theology. What can I say? I’m a historian.

The explanation is simple: Luther grew up with a Bible that didn’t have Matthew 6:13b. It is not in the Latin Vulgate, the official Bible of the Middle Ages. If you are a Catholic, or ever attend a Catholic Mass you are probably used to saying the Lord’s Prayer without this little concluding riff.

On the other hand, English-speaking Protestants pretty much always say it — even if the NRSV and the NIV both agree with the Vulgate and leave it out. (Apparently it doesn’t appear in the earlier manuscripts of Matthew. O well.)

Even if this line was not originally part of the Lord’s Prayer it is a fitting and useful conclusion. It is what you really ought to be thinking, or saying, as you come to the end of all the topics Jesus said to pray for.

The Heidelberg Catechism does a great job of showing why.

Wrapping up our prayers by saying that the kingdom power and glory belong to God alone does two very important things:

- First it reminds us of who the God is to whom we pray.

- Second it reminds us of what our motives in praying really ought to be.

We have confidence to pray at all, and to pray for these particular things, because of who God is. God is king of all, with the right to do anything he wants. God has all the power needed to answer any prayer we could come up with. This God actually loves us and wants to give us these things — otherwise, this sovereign, powerful God would never have, in Jesus, invited and commanded us to pray for them.

In the words of the Catechism,

“We have made all these petitions of you because,

as our all-powerful king,

you are both willing and able

to give us all that is good;”

And if we really think about who we are as subjects of this great king, we should be asking for what brings God glory — not just for what pleases us. That is why the Lord’s Prayer began, not with our needs but with God’s holy name, God’s kingdom, and God’s will. Now at the end we put all of our needs and requests in the greater context those terms define.

As the Catechism puts it,

“and because your holy name,

and not we ourselves,

should receive all the praise, forever.”

If it does not build God’s kingdom, lead us to humbly acknowledge that only God’s power can do it, and bring God’s glory to a greater shine, then we probably shouldn’t pray for it.

What do you find helpful — or problematic — about ideas of God’s kingdom, power, and glory today?

____________

The coolest thing ever would be if you shared this on your Facebook page.

If you don’t see the sharing buttons below, click here and scroll down.

Gary, in the Catholic church we’ve been praying For thine is the Kingdom, the Power and the Glory for a very long time. I’m going to guess since Vat.II. 🙂

Thanks Tracy (this is Tracy, right?)

Okay, looks like you caught me. I think the text of the Mass I once studied was pre-Vatican 2 — and the breviaries I’ve used are definitely that old. But my recollection of Masses I’ve attended over the years was that they stopped short of “the kingdom, the power, and the glory”, had some other bits of liturgy, then came in with it half a minute later. Does that sound right? I don’t get to Mass that often unless I’m on retreat.

Sorry for the blunder!

Okay, now I’ve done a quick peak, first into my Pre-Vatican 2 “Monastic Diurnal” (actually the excerpt in The Kneeling with Giants Reader), and a website with the liturgy of the Mass.

Monastic Diurnal: The Lord’s Prayer simply stops at “But deliver us from evil.”

Mass: The first instance I found looks like this:

All: Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name;

thy kingdom come; thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread;

and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us;

and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.

Priest: Deliver us, Lord, from every evil, and grant us peace in our day. In your mercy keep us free from sin and protect us from all anxiety as we wait in joyful hope for the coming of our Savior, Jesus Christ.

All: For the kingdom, the power, and the glory are yours, now and forever.

I’m neither a liturgical historian nor a Catholic, and would be grateful to anyone who knows the story of how this split usage of the concluding line evolved in the Roman Catholic Church. To my eye it looks like a nod to the the lack of this line in the best Biblical manuscripts and another nod to its presence in the Church’s praying since the later Biblical manuscripts.