Dear ______:

Sorry for the delay in writing back. What can I say? I was swamped.

I’m glad to hear your classes are also requiring you to read things that aren’t primary sources, and aren’t introductory text books.

The interesting stuff in any field is happening in the current scholarship: the monographs and articles. These are likely to be assigned only in your more advanced elective courses.

How should you read current scholarship?

In a word: Strategically.

Reading Scholarly Studies

You need to learn how scholars present their work in publications. You can use your time best by reading according to the conventions of the genre. In a sense you should (ahem.) study studies rather than simply reading them.

Of course you could approach them the first grade way: start with the first sentence, plow on, sentence by sentence, mouthing each one silently in your head, till you get to the end.

The problem with that is you’ll be bored, you’ll be lost, and you’ll miss the very interesting and useful stuff that the author slaved over for years.

A Sample Case

To highlight the need for a strategic approach, imagine the following:

Let’s pretend you have a seminar in a seminar on American Church history. This week the class will spend its three hour session discussing E. Brooks Holifield’s God’s Ambassadors: A History of the Clergy in America.

- The first problem is you didn’t actually read the book. The week was a total washout.

- The second problem is there are only seven people in the seminar. Your silence will be noticed.

- Third problem: your class starts at 2:00. It is now 1:00.

In this scenario you would be totally sunk with the first grade reading strategy. How will you make use of that one precious hour?

Time for strategic reading, aka “academic triage”

The clock is ticking.

Think back to a M.A.S.H. rerun: Suddenly overrun with wounded soldiers, Hawkeye and the gang had to think quickly about who to treat in what order and in what way.

That’s triage. They offered medical care strategically to save as many as possible.

So let’s triage your reading so you get as much learning as possible. Let’s see how much class preparation you can squeeze into your single, seemingly inadequate hour.

1:00. Read the Syllabus.

First figure out what you should be looking for in the assigned book. This book covers Protestant and Catholic clergy for about three centuries.

Your syllabus shows you two important things:

- Unlike the book, the class focuses only on Protestantism.

- In this part of the semester you are dealing with the late 19th century.

Discovering that took about a minute. It saved you hours. You’ll see.

Take another minute to think up questions about Protestant clergy from 1850 to 1900. What would be interesting to know? You might want to jot the questions down.

1:02. Read the Cover.

Of course you should not judge a book by its cover. But the cover of an academic book can teach you a lot.

The publisher may not have invested heavily in the picture on the front, but you can bet they worked hard on the back.

You’ll find three things on the back that are worth a few minutes of your triage time.

First you’ll find a brief author bio. That can help you put the book in context.

- Is the book is by a prominent scholar with a weighty record of publications and awards?

- Or is it by someone young, fresh from grad school?

- Does the author work at a top university where research is the major focus?

- Or is the author on the faculty of a small sectarian school that will only support a party line?

Just take it in. Know who you are dealing with.

Second you’ll find a brief summary of the book, probably by the author. One or two paragraphs will tell you about the main question that prompted the book, and give you some hints as to its main conclusions.

This may not be the stuff that lures bookstore browsers to drop $32, but for you it’s gold. Read it twice. Now you know what the book is about.

Third you will find what are technically called “endorsements” but are usually referred to as “blurbs.” The publisher will have sent advance copies to reasonably well-known scholars in exchange for a few complimentary sentences.

This too is gold for you. The blurbs tell you what smart people in the field say is good about the book.

Well those were four well-spent minutes. What’s next?

1:06. Read the Table of Contents.

Now open the book, but don’t start reading. Starting to read now would be like driving off for your vacation without either a map or a GPS. You need to know where you are going.

Head for the Table of Contents. This is your official map to the book. Take a few minutes and study the chapter titles and subtitles.

Ask yourself two questions:

First, what do you learn about how this author approached the topic at hand? The book has a structure, and the flow from chapter to chapter is intended to teach you about the subject.

Second, and most important, which chapters are relevant to you? It may all be interesting. It may amount to an integrated argument that hangs together brilliantly.

But from what you saw in the syllabus, only one chapter is clearly relevant:

5. Protestant Alternatives, 1861-1999.

Good thing you read the syllabus and the map first. You just saved yourself hours and hours.

Or rather, since those hours were gone before you started, you just figured out how best to spend the last 50 minutes before class.

1:10. Skim the Introduction.

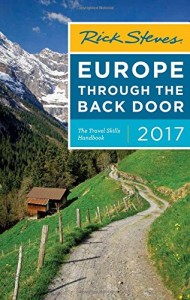

You may be tempted at this point to jump to chapter 5. Don’t. First find a tourist’s guide book.

When you plan your European vacation, you pick up a travel guide. It helps you know a bit of history, a bit of geography, famous places, good restaurants — all kinds of stuff. It helps you make good use of your vacation time.

When you plan your European vacation, you pick up a travel guide. It helps you know a bit of history, a bit of geography, famous places, good restaurants — all kinds of stuff. It helps you make good use of your vacation time.

In an academic book, the Introduction is like your travel guide. It may be dry but it is there to help you.

This is how academic books are organized, so work with me.

You don’t have time to read the whole Intro. Do a strategic skim.

- Read the first paragraph. It is likely to orient you to the book and its purpose.

- Then read the first sentence of each paragraph. The people who write academic studies did well in high school English. They learned that every paragraph needs to start with a topic sentence, followed by the supporting information.

- So skip the supporting information. Just the topic sentences will take you through the main argument.

- Eventually you will find the place where the author gives you either a sentence or a paragraph summarizing every chapter of the book. This too you should read.

- Then read the last paragraph of the introduction were the author tells you why the book is worthwhile.

Those 15 minutes gave you a much richer sense of the book as a whole.

Do you see what you’ve been doing?

- The cover gave you a bird’s eye view.

- The Table of Contents gave you a map.

- The introduction served as your tourist guide.

Every step has oriented you at a deeper level.

Now you are ready to read. Sort of.

1:25. Skim the Crucial Chapter(s).

Finally it is time to read chapter 5 — or whatever section of your actual book you now know to be most relevant to your purposes.

Don’t make the mistake of bringing out your old first grade reading strategy.

Instead, do what you just did with the Introduction. Skim.

- Read the first paragraph to orient yourself to what is coming.

- Then flip to the end and read the conclusion to find out what the author thinks were the chapter’s most brilliant insights.

- Then go back to the beginning and read the first sentence of every paragraph of the chapter.

Look back to the questions you jotted down in minute 2, after looking at your syllabus.

- Any answers emerging?

- Any observations you can add?

- Any questions you wish you could ask the author?

With almost half of your minutes left to go, you are already much better prepared for class than you thought you would be.

By triaging the book according to the standard form of an academic publication, you quickly got enough of what you needed to make it through class without embarrassment.

What will you do with your last 25 minutes?

1:35. Read the Crucial Portions.

Now it really is time to read. But read selectively.

Because you triaged your book so well, you know what parts of the crucial chapter are really useful, really interesting, or really confusing.

Go back to those sections. Read them line by line. Make a few summary notes. Jot down some questions you might ask your professor and your fellow students.

If time permits read the first and last sections of the other chapters.

1:50. Skim Other Interesting Bits.

Hey look! You still have ten minutes to go. What will you do?

You have now become aware of other important parts of the book. There is material on the relevant period and topic scattered in other chapters.

Go and find that stuff, and skim what you can. Just take it in, becoming aware of as much as you can.

2:00. Now go to class.

You are actually pretty well prepared. You might even be better prepared than if you’d spent the week trying to read every sentence in order.

Take your book and your page of notes to class. You’ll find that you have useful things to say when the prof calls on you. You may have some things you are really eager to share. Or you may want to ask those questions you jotted down.

And you have every right to participate. You read the assignment.

You didn’t read it by a first grade standard. You read it by a graduate school standard.

What if you still have a whole week to read the text?

Hopefully most of the time you won’t have to triage your readings at the last hour.

What will you do, though, if you have a whole week ahead of you before discussing the book in class.

Will you bring back your first grade standard and plow through line by line?

No. Please, no.

Read like a good little graduate student. Take the first hour of your study time, a week before the class, and do that very same triage you would have done if you’d put studying off to the last hour.

After triage, you will be able to spend the week studying the details — and much more effectively. If you have multiple hours to invest in preparing for class, you can spend them really well, getting to know it at a much deeper level.

Happy reading,

Gary

————

I’d love to know your thoughts on this kind of reading in the comments.

And if you found the post helpful I hope you’ll share it!

————

This post contains affiliate links.

I’ve found academic reviews also to be very good resources. Many universities and colleges have subscriptions to online journals where you can find these sorts of things.

One word of warning though: the reviews will have the opinion of the book by the reviewer. Not everyone will have the same opinion. However, most reviews will give you a good synopsis of what the book is about and the conclusions the author comes to.

Excellent point — Are you reading my mind or peeking ahead to coming posts?

Oops! I didn’t mean to give away spoilers.

I could have used this for some of your classes 😉 Thanks for the insightful guidance.

Hello Seth! Great to hear from you here on the blog.

It may have been after your time, but for many years I did a session in M.Div. orientation called “Grad School 101,” and it included the approach in this post.

As always, excellent advice. Journalists read this way, too (at least those who read…)

Thanks Gary! As we were chatting about in another post’s comments, it is one of several reading strategies. It isn’t one for pleasure reading, but a great way to move through material expeditiously.

Blessings,

Gary