One peril of visiting a new church comes when it is time to pray. At least if the congregation of a traditional flavor they will wrap up with something like “Now let join our voices in the prayer Christ himself has taught us, saying…”

It all goes fine for a while:

…Father…

…Name…

…kingdom…

…will…

…daily bread…

But then that awkward moment: what will we ask God to forgive?

If you are visiting your own brand you probably know what to expect:

Presbyterians?

Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.”

Catholics, Episcopalians, and Methodists?

Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

Progressives?

If the church is trying to be up to date, they may have taken hold of the recent translation by the English Language Liturgical Consultation:

Forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us.”

I teach at a Presbyterian seminary with a lot of Methodist students. That ecumenical version brings unity — everybody is equally uncomfortable.

The new translation of the Heidelberg Catechism of the RCA, the CRCNA, and the PC(USA) has “debts” and “debtors.” Were they just toeing the party line?

Actually they were sticking with the task of translation — though when the Catechism quotes Scripture they tended to use the NRSV. That is, they gave a scholarly English translation of the Greek, rather than giving an English translation of the German translation of the Greek.

After saying that we should pray for everything we need just as Christ taught us in the Lord’s prayer, the Catechism continues

119Q. What is this prayer?

A. Our Father in heaven,

hallowed be your name.

Your kingdom come.

Your will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our debts,

as we also have forgiven our debtors.

And do not bring us to the time of trial,

but rescue us from the evil one.

For the kingdom

and the power

and the glory are yours forever.

Amen.

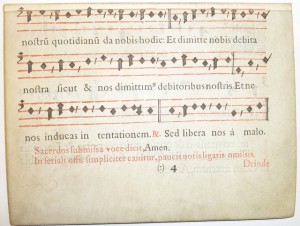

Even if the English translators had tried to render the German’s meaning instead of the NRSV, they would have come up with “debts” and “debtors.” The original 1563 German had “Schuld”/“Schuldigern” which comes out nicely to “debts”/“debtors,” and the Latin translation of the same year went with “debita”/“debitoribus.”

So why the three versions of the prayer?

Though I’ve never looked too closely into the history of the versions of the Lord’s Prayer used in worship, here’s how I suspect we ended up with “debts,” “trespasses,” and “sins.”

There are two version of the Lord’s Prayer: Matthew 6:9-13 and Luke 11:2-4. They differ on many points including this.

- In Matthew, Jesus asks God to forgive us our “ὀφειλήματα” as we forgive our “ὀφειλέταις”. That is most straightforwardly “debts” and “debtors” though I’ve seen it said that it can be taken as a reference to “sins”.

- In Luke, Jesus asks God to forgive our “ἁμαρτίας” as we forgive those “”ὀφείλοντι” to us. That is God forgives “sins” and we forgive those “indebted” to us. But this word, commonly translated “sin,” has a root meaning of “missing the mark.” Think “wandering from our target.” Think “trespassing.”

(It seems a little surprising that Catholic practice uses “trespasses” since the Vulgate of Matthew has “debita”/“debitoribus” and the Vulgate of Luke has “peccata”/“debenti”. I’d love it if a learned reader would enlighten me on this.)

So, correct me if I’m wrong, but it appears English liturgical use of the Lord’s Prayer works out like this:

- If your church prays about “debts” and “debtors” they simply follow Matthew’s version of the Lord’s Prayer.

- If your church prays about “trespasses” they follow Matthew’s framework for the prayer, with a term based on that used by Luke for our transgressions against God, apparently using the same term for symmetry regarding our transgressions against each other.

- If your church prays about “sins” they follow Matthew’s framework for the prayer, with Luke’s explicit term for our transgressions against God, apparently using the same term for symmetry regarding our transgressions against each other.

————

I’d love to hear from you in the comments: Do you favor “debts” “trespasses” or “sins” — and why?

Kenneth Bailey, in his book Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes, points out that in Aramaic Jesus may have used the word khoba, which means both debts and trespasses (he presumes that Jesus preached in Aramaic, and it was the authors of the Gospel who utilized Greek). Neither Greek nor English have a word that includes both meanings; however, he says that whichever word we use, “the faithful need to remember that they are asking for forgiveness for failing to fulfill what God requires of them (debts) and for their failure to do the right thing when they did act (trespasses)” (pg. 126).

Besides the debts/sins/trespasses problem, the next bigger is: what does επιοὐσιον mean, and why is it left out of English translations?

Thanks Fr. Dustin — a cool insight from Bailey’s book!

In the Gospel reading a few weeks ago, when the Disciples asked “How shall we pray”, Jesus used the word “sins”, not trespasses.

How can the Church change the very words of Jesus?

In the liturgy, “sins” is used repeatedly –

“I confess to Almighty God . . . . . that I have greatly sinned.”

”…..look not on the sins of your church but . . . . “

”…….we shall be free from sin and safe from all distress….”

Hi Tom:

I think if you check out the article above you’ll see it isn’t really a matter of two different Gospels recording very different versions of the Lord’s Prayer, in the course of which Jesus uses three different words for what gets forgiven — and those words get translated in various ways from Greek to English.

Interestingly it is in Luke where the disciples ask Jesus how to pray, but the Churches pretty universally use Matthew’s version of the prayer in their liturgies!

Blessings,

Gary

Just FYI Gary, the OA 12-step version uses “strength” instead of “bread.” Probably as a means of leading us not into temptation. (I can find it myself!) Cheers, Amy

Thanks, Amy! Very interesting contextual “translation”. Gets right to the point, and avoids a difficult problem.

Hi Amy,

To use “strength” instead of “bread” is a very interesting theological twist. With the use of επιοὐσιον (literally, “super-substantial,” but left out of English translations) next to αρτος (bread) in the original Greek “Our Father,” it’s clear that the original intent was that it was a reference to the Eucharistic bread. Perhaps they were purposely trying to remove Christian references?

Christian translators trying to remove Christian references does not make clear sense to me.

The word appears only here in Scripture, and only once outside (post-biblical) Christian literature in antiquity — according to Foerster’s lengthy article in Kittel this was a papyrus, in a list of material things including chickpeas!

The meaning seems difficult to get to, though “super substantial” was favored in the Latin Middle Ages when it was taken as a Eucharistic reference if memory serves.

After weighing too many options, the article in Kittel settles on the kinds of meaning that prominent English translations have favored: meanings “not of time but of measure” aiming either to amount (“for today”) or in the direction of “necessity” — the bread we need right now, our sustenance,

I did some quick research. Here’s what I discovered:

Origen (2nd century) links the bread with the Eucharist. As for super-substantial, he says that it’s an indication that’s it’s more than just regular food. He writes, “The ‘true bread’ is that which nourishes the true humanity, the person created after the image of God” (On Prayer 27.2).

St. Cyprian (3rd century) writes, “Now we ask this bread to be given to us today, lest we who are in Christ and receive his Eucharist daily as the food of salvation should be separated from Christ’s body through some grave offense that prohibits us from receiving the heavenly bread…” (Treatises, On the Lord’s Prayer 18).

St. Jerome (4th century) writes, “In the Gospel the term used by the Hebrews to denote supersubstantial bread is maar. I found that it means ‘for tomorrow,’ so that the meaning is ‘Give us this day our bread’ for tomorrow, that is, the future. We can also understand supersubstantial bread in another sense: bread that is above all substances and surpasses all creatures.” (Commentary on Matthew 1.6.11).

Tertullian (3rd century) wrote, “We should rather understand ‘give us this day our daily bread’ in a spiritual sense. For Christ is ‘our bread,’ because Christ is life, and the life is bread. “I am,’ he said, ‘the bread of life.’ …Then, because his body is considered to be in the bread, he said, ‘This is my body.’ When we ask for our daily bread, we are asking to live forever in Christ and to be inseparably united with his body” (On Prayer 6).

These all come from centuries after Jesus — though Origen was born in the 2nd century, he reached adulthood and wrote in the 3rd. They represent Christian attempts to discern meaning in a very obscure word used once in the Bible. Had they known about the one other use of the word in antiquity (the papyrus cited in Kittel as I mentioned) they might have been less likely to draw a spiritual meaning from it.

Very true: had they known, they may have come up with a different interpretation. The study of the evolution/development of doctrine is fascinating. The beauty of dialogue through blogs, such as the fine one you have here, and studies like Kittel’s, means there’s always something more to learn to draw us deeper into the mystery of Christ!

I prefer the Hebrew version from Matthew, which reads “… forgive us the debt of our sins as we forgive the debt of those who sin against us…”

Because Yeshua/Jesus died to pay the debt of our sins, that we owed to Him/God…

Dear David:

Thanks for chiming in on this old but frequently visited post.

I’m curious: Are you looking at a translation from the original Greek into Hebrew, or an English translation that tries to take account of Hebraisms in the Greek?

Gratefully,

Gary

So, I’m reading an article tonight that suggests that William Tyndale may be to credit (or blame) for “trespasses.” He was the first to translate the Bible in English (against the wishes of King Henry VIII. He preferred using “trespasses” in Matthew 6’s Lord’s Prayer (forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us) even though the greek as you state is more accurately translated “debts.” He had successfully hid out from authorities for about ten years for his crime of translating the Bible, until someone finally outed him. He was executed in 1536. By 1611, the King James version came out which had “debts” and not “trespasses.” Methodists, Episcopalians and Anglicans might very well be praying “debts” if William Tyndale’s interpretation of “trespasses” wasn’t used in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer. But Tyndale’s interpretation won out in this book. How in the world American Catholics say “trespass”– that’s a mystery. I’m not even sure if this is true, but I read it on the internet so it might be. Ha! It’s a good story even if it’s not true– and if for nothing else, as a Methodist, it reminds me that people in the past like Tyndale were so passionate about making the Bible accessible to people that he gave his life for it.