Dear ______:

So classes have started. I love the feeling of new classes. It is like a whole new world is about to open up — all kinds of potential for new discovery.

Sorry to hear that your Old Testament class is giving you trouble though. I’m not exactly surprised, but that doesn’t mean I’m not sympathetic.

I’d have to hear more, but from what you say I think your struggle is a very common one. If its meaning seems closed off and locked up, rest assured you are not the only one who thinks so.

Trouble with Old Testament

It is not the old struggle of what to do with the violence of the OT and things like that. The trouble you face is due to a mismatch between your level of previous understanding and the kinds of issues your professors are addressing.

In any academic program the professors have to make some assumptions about the level at which they will teach their subjects. And many professors, in any field actually, get most excited about teaching things at an advanced level. Or we can forget what it was like to know virtually nothing about the field.

The students are in a totally different place.

A few generations ago, new seminary students came knowing a lot of Bible basics from Sunday School. Their undergraduate work might have included academic study of the Bible.

Today that is not often true. Many are like you, having only come to a growing faith as adults. Often their first reading of the Bible happens in a seminary-level Bible class.

If the student is underprepared, and the professor aims high, the results can be disastrous.

When I took my first Bible classes the professors focused on what is called “higher criticism.” That meant traditional positions were called into question — like Moses as author of the first five books, or one guy named Isaiah writing the whole of the book called Isaiah. There are excellent reasons to teach those things.

But higher critical questions had odd results among underprepared seminarians. One group nearly worshipped the Bible— and intro Bible classes seemed to topple their idol. Another group already assumed the Bible was pretty irrelevant — and intro Bible classes seemed to confirm their opinions.

If seminary education leaves both of ends of the spectrum less in love with the Bible’s teachings, that is a problem.

So I don’t want that to happen to you. Here’s my suggested plan.

Get to know the Story of Scripture

First, even if it seems almost too late, get to know your way around the Bible. The OT tells a story — an amazing story of God’s grace and faithfulness.

Read the Bible, apart from class assignments, just to listen to that story.

- Find and learn the outline. Write it out on paper.

- Discover the main characters, and place them on the outline.

- Match each book to the part of the outline it covers.

Good things happen when you know the Bible’s big story. All the little stories within it begin to become part of you.

Over time you will find that the Bible’s story is the story of your own life in relationship with God. It becomes a resource for thinking about your life, and the world, and God. The story begins to give shape and meaning to everything.

Trust me on this. It just has to grow on you.

If you want a great resource to help you get there quickly, check out Henrietta Mears’ classic book What the Bible Is All About. It won’t help you in class. But it will help you get ready for your education.

Learn to Pray the Text

Second, always try to weave prayer into your encounters with Scripture. John Calvin would tell you that you need to pray for God’s Spirit to shed light in your mind or you’ll never learn what Scripture is there to teach you.

Invite God to be present, and to speak to you as you read the Bible each day.

And beyond that, find ways to let the Bible’s words teach you to pray. The Psalms are a rich treasury of ancient prayers. Calvin would tell you that they are there to teach you everything about prayer.

He thought the Psalms were like an anatomy text book for the human soul. Everything you and I face is prayed about somewhere in the Psalms. It gives you permission to pray about anything and everything.

Then the Academic Questions

Finally, once you know the story of the Bible and regularly encounter God through reading it, then you are equipped to face the academic questions your professors are pitching you.

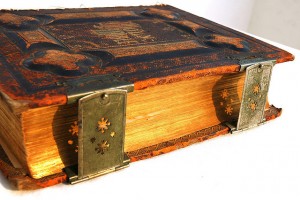

Once you know and love the Bible you naturally want to think about how it came to be, and the ancient layers that you find within it. You’ll be ready to see how every era brings new questions and new insights to the Book of Books.

And since you know the God you meet there, no human question can topple your faith.

Blessings,

Gary

——

Your turn: What helps you find life and faith in the Old Testament?

Let me know in the comments below.

(This post contains an affiliate link.)

Why would seminary professors be teaching higher criticism at a seminary to begin with?

A seminary has a particular task: to train clergy. Seminaries also have a theological unpinning that should be driving what and how they teach.

The Christian creed (Nicene-Constantinopolitan) says that Christ was crucified, suffered, buried and rose again “according to Scripture.” If anything this should be the primary focus of Old Testament courses.

While it’s probably true that Moses didn’t write the Pentateuch, it seems a seminary professor would be letting the students, and his church, down if he’s not teaching how Christ is found in the Old Testament. There are many ways of doing this: allegorical (Alexandrian), typological (Antiochene), or even the “Bible as Literature” would be more helpful.

The goal, in the end, should be that every student can explain how it is that all this happen to Christ “according to Scripture.” Should it not?

Thanks for your comments, Fr. Dustin.

Some seminaries, I’m sure, focus solely on training clergy, but many in North America have broader purposes than traning clergy. The one I attended trains many who aim from the beginning for an academic vocation. The one where I teach also trains those who seeking non-ordained service in God’s mission.

But even if a seminary has a focus entirely on clerical formation, most are providing an accredited graduate degree that brings people as deeply as possible into a range of theological disciplines.

When it comes to teaching Scripture, seminaries connected with mainline Protestant denominations (and I suspect many Catholic schools, as well as university divinity schools) will naturally include teaching how Scripture has been approached in Western scholarship for the last two or three hundred years. In many denominations these approaches have been formative, and indeed have been useful solutions to problems seen in older approaches. I think someone with a Ph.D. in either testament would find it intellectually and theologicaly irresponsible to not teach about higher criticism.

The challenge in much of the world of seminary education is to sympathetically teach also the ways Scripture was approached before the Enlightenment. In much of the Western world, especially in academic circles, such approaches are usually assumed to be intellectually untenable. Such judgements are often based on polemics rather than on reason or experience, but that is the state of things.

Blessings,

Gary

I think “higher criticism” is OK as long as it’s balanced with a canonical approach that focuses on God’s action in our lives.

I’m finding that at least some folks are curious about how the Bible came to be the Bible. I’m also finding that at least some folks have unnecessary difficulties with the Bible because they think “believing in the Bible” means opposing science.

Thanks Gary. You are discovering that the pastor has to educate on multiple fronts.

I think if we start with a living faith, going to Scripture in ways that mesh with the historic Christian faith, that lays a good foundation. That is, we need to teach the practice of regular reading of the Bible, as well as more prayerful approaches like lectio divina.

When those kinds of engagement are in place, healthy questions will emerge, and the ground is laid for other kinds of teaching. Sometimes the questions are answered by historical criticism. Sometimes they are answered by canonical cricicism. Sometimes they are answered by introducing what Steinmetz calls “pre-critical” approaches, whether rooted in the Patristic era, the Middle Ages, or the Reformation.