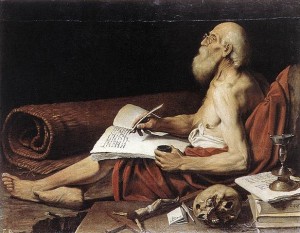

Today the Western Church commemorates St. Jerome (c. 347-420). What a complicated fellow. First passionate about secular literature, he gave it up to be a scholar of the Bible and a leader in the ascetic life. Absolutely counter-cultural — but maybe this Doctor of the Church still has things to teach us.

He was controversial

Like so many in his era he had a powerful ascetic bent. The body was not his priority; I read somewhere that after baptism he didn’t see the need to bathe any more.

His willingness to provide women with spiritual counsel caused controversy in Rome when a woman he was guiding in the spiritual life died of his ascetic hardships.

He clearly loved women, causing controversy for his close association with a widow named Paula, eventually setting up life as a hermit in the holy land — but close enough to Paula to provide her spiritual counsel.

Sexuality? He was forced to admit that marriage was, after all, a good thing — because it produced more virgins.

Think about that one for a minute.

He was scrappy in controversy, but that didn’t mean he always stayed consistent. He loved the spiritual allegorical interpretation of the Bible done by Origen of Alexandria, translating some of Origen’s works for the West — until he didn’t like Origen any more and wrote against him.

He had brilliant insights

Jerome’s influence was huge in the Church at large.

He’s the guy who realized that the Latin-speaking West needed a solid translation of the Bible in their own language.

He’s the guy who realized that since the Old Testament had been written in Hebrew, a Christian could, and should, translate it from the original — rather than providing a translation of a translation by starting with the venerable Greek Septuagint.

He’s the guy who realized that a Christian could, and should, learn Hebrew to do that job — something that had hardly been attempted in the Christian world apart from Origen of Alexandria.

He did world-changing work

Maybe he didn’t translate the whole Bible himself, but he was the crucial figure in the process that produced the Latin version known as the Vulgate. The term indicated that this was in the people’s own speech, the common tongue. It remained the standard text of the Bible in the west for more than a millennium — all through the time Latin was the people’s language, and on through the time that Latin was the language of scholars.

For Protestants it was displaced by new “vulgate” or vernacular translations in the sixteenth century.

Learning from Jerome

Actually there is a lot to learn from Jerome. We can certainly learn from his passionate devotion to the study of Scripture — in the original languages, no less — and his commitment to putting the Bible and commentaries in the people’s language.

I’m not quite sure what, but I suspect even Jerome’s asceticism has something to teach our sex-obsessed and generally self-absorbed culture.

————

I’d love to hear from you in the comments: What do you think we can learn from St. Jerome, and those like him, from centuries past?

————

Check out my other posts on the saints by clicking here!

What was St. Jerome’s argument for translating from the Hebrew?

Doesn’t the use of the LXX by St. Paul and other early Church Father’s act as a “stamp of approval” on the Greek (not to mention that the LXX has more Christological typology than the Hebrew). In this way, I understand the Church act as an editor, in a similar way a modern editor doesn’t publish the first MSS an author sends him – the MSS get’s edited.

Perhaps this becomes a complicated question. After all, the next question that follows is: is the Holy Spirit acting through the autographs (the original MSS), or through the editorial and canonization process of the Church. In short, if another letter of St. Paul were to be found, would it be accepted, or rejected on the grounds that the Church didn’t preserve it?

I think Jerome was probably motivated by the need for people to have the Bible in their own language. With that translation task before him the question for the OT is “What will give me the clearest access to the thought of Moses, David, Isaiah, etc?” Like the translators of the LXX, Jerome went to the earliest available form of the text.

There is a fascinating tendency in the church to become devoted to particular translations. It happened with the LXX. It happened with the Vulgate — keeping it the Catholic Church’s authoritative text long after Latin was a nearly unknown tongue. It is active right now in English — just Google “King James Only” some time and see how much authority is vested in a translation into language no longer in use, and based in some cases on manuscripts that scholars readily reject.

Thank you for your response. You always give me things to think about!

I agree with St. Jerome: we need the Bible in an understandable language. Unfortunately the Orthodox Church is still struggling with that issue, despite the tradition of Ss. Cyril and Methodius. In Greece services are still in Byzantine Greek, and in Russia services are still in Church Slavonic. Here in America it varies, depending in the jurisdiction and parish.

Yet, perhaps, there is still grace: “[The Pilgrim said,] ’I cannot accept it [a Bible given to him]. I am not used to Church Slavonic and don’t understand it.’ But the monk went on to assure me that in the very words of the gospel there lay a gracious power, for in them was written what God Himself had spoken. ‘It does not matter very much if at first you do not understand; go on reading diligently. A monk once said, ‘If you do not understand the Word of God, the devils understand what you are reading, and tremble’…” (The Way of a Pilgrim).

Nonetheless, I’m still convinced that the LXX should act as a guideline (a Canon of Truth, perhaps?) for translations into other languages, precisely because of its unique role within Church History. Early English translations from the Hebrew were problematic because they were from the Masoretic text – a medieval version of the Old Testament, which had undergone changes precisely to remove Christian passages (starting with Rabbi Akiva and Aquila). The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has also shown that some ancient Hebrew versions of the Old Testament, which weren’t otherwise preserved, favor the Septuagint reading rather than the Hebrew Masoretic reading (I’ve seen percentages of LXX vs. Masoretic vary, so I won’t make a claim of percentage). The Peshitta (2nd century Christian Syriac translation) also seems to agree with the LXX, rather than the Masoretic text.

Can the grace of Jesus Christ still show through, despite translation errors? Absolutely. I guess all this is to say, however, that I strongly believe we need accurate English translations, but I think what we should carefully consider the source from which we are translating (if we are translating for church/devotional reasons).

In an article on the website of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, Rev. George Mastrantonis notes that the LXX is used as the official OT in Orthodoxy, but also notes that the OT was written by the Prophets in Hebrew and Aramaic and states that “God’s inspiration is confined to the original languages and utterances, not the many translations.”

Here’s the link: http://www.goarch.org/ourfaith/ourfaith7068

I don’t believe you are quite right about the nature of the Masoretic text. For well-rounded scholarship on the issues I’d recommend the Cambridge History of the Bible.

You’re right, I made a mistake (sorry!). Rabbi Akiva and Aquila made a new translation of the *Greek* in response to the Christians using the LXX. Nonetheless, we still have the problem of, which *original* text? The Dead Sea Scrolls from Masada that support the Masoretic text, or the Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran that differ from the Masoretic text (generally agree with the LXX)? And then there’s the Samaritan Torah with its significant changes, which is also supposedly handed down from Moses.

Very nice find from the Greek Archdiocese website! Though I’m surprised he said that, after all, St. Philaret of Moscow contradicts him, “In the Orthodox teaching of Holy Scripture it is necessary to attribute a dogmatic merit to the Translation of the Seventy, in some cases placing it on an equal level with the original and even elevating it above the Hebrew text, as is generally accepted in the most recent editions” (On the Dogmatic Worthiness of the Septuagint [Moscow, 1858]).

What an interesting discussion we’re having. It’s always good to step back and think about things a bit. At any rate, if you’d like to add another word, I’ll let you bring it to a close.

Sorry, one last story from the Orthodox tradition, which I think you and your readers will find fascinating:

From wikipedia: “According to a tradition in the Eastern Orthodox Church, Simeon [Luke 2:25-25] had been one of the seventy-two translators of the Septuagint. As he hesitated over the translation of Isaiah 7:14 (LXX: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive…” Many modern scholars read “young woman” for “virgin” in the Hebrew), an angel appeared to him and told him that he would not die until he had seen the Christ born of a virgin. This would make him well over two hundred years old at the time of the meeting described in Luke, and therefore miraculously long-lived.”

You can also find the story on the website of the Orthodox Church in America: http://oca.org/saints/lives/2013/02/03/100409-holy-righteous-simeon-the-god-receiver

If nothing else, it illustrates a tradition within Orthodoxy that recognizes the inspiration of the LXX.