Dear ______:

Dear ______:

Last time I wrote I was full of athletic metaphors — the Olympics were a big deal at our house. Now I’m tracking backward from the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat, and thinking about how thriving in seminary is like learning to swim.

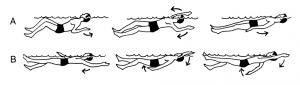

We all start out with the flailing dog paddle of survival. But if you are going to be a competent swimmer (more competent than me that is) you need to move on and learn several distinct strokes.

- Crawl.

- Backstroke.

- Breaststroke.

- Butterfly.

Each one has its own precise motions.

Learning each one takes you back to the beginning.

And if you take swimming seriously, actually joining the school team, you have to keep each one straight.

- Do the dog paddle in the freestyle event and you are gonna come in last.

- Try the crawl in the 50 meter butterfly event and you may come first but you’ll be disqualified.

So how is that like seminary?

Two Ways Seminary Is Like Swimming

When I wrote about seminary being hard for almost everyone it was because of two ways seminary is like swimming:

- You have to master several very different strokes.

- You have to remember to do the proper stroke in each event you enter.

1. Learning the Strokes

Okay, keep the lame metaphor in mind.

Learning the History Stroke

Now consider my intro Church History class. I want my students to learn some of the skills that historians bring to their work.

Yes, they need to learn the big picture story and they need to learn who the key people and issues were throughout.

But I really want them to learn to take a text from the past and see what they can discover first hand about what Christianity was way back then. Do that well and they will be able to think clearly about why Christianity is the way it is now.

So I make them read “primary sources” (documents from the period we are studying), say Athanasius of Alexandria.

And I make them write papers where they use those sources for evidence as they make arguments about the past.

I tell them to set aside “secondary sources” (writings by modern historians) and be like the folks in the Renaissance whose motto was “Ad fontes!” (“To the sources!”)

- They need to analyze sources.

- They need to declare the point they want to prove.

- They need to make a case using evidence from the sources.

These are things historians do.

Learning to swim in seminary means they need to take the time to learn the history stroke, even when it is hard work.

Learning the Theology Stroke

Then, some years, I was called upon to teach the introductory theology sequence. The skills of a theologian are different from those of a historian — though ideally the one builds on the other.

What Christians say about God and salvation, the official and unofficial teachings of the churches on key elements of the faith, are all parts of an ongoing conversation.

This includes history, since our sisters and brothers of past centuries are really our mothers and fathers in the faith. Honoring our parents means listening with respect, even if we differ. And frankly they were often very insightful.

That is, learning the history stroke first is useful — it keeps pastors from saying silly and wrong things about the past. But the theology stroke is quite different.

Learning the Ministry and Bible Strokes

Students learn a completely different stroke when they take a preaching class. It is about practical ministry, communicating the faith to living people. Still, you need some mastery of the theology stroke. And the Bible stroke too of course.

Pastoral care is just as much ministry as preaching, but again it is a completely different stroke. Think “pulpit” vs. “hospital bedside.”

Greek and Hebrew, biblical theology, exegesis, all are parts of the Bible stroke. And the Bible stroke is the foundation of all.

Though you’ll find it goes full circle: you can’t deal wisely with your Bible unless you have some mastery of the strokes of history, theology, preaching, and pastoral care.

2. Using the Right Stroke at the Right Time

The seminarian’s challenge is learning when to use each stroke you have learned.

- Into my Church History class comes a new student who just had a powerful conversion. He finds Athanasius inspiring. His paper is all about his own faith and how Athanasius calls him to go deeper.

- In comes another student, an experienced lay pastor. She has preached a lot. Her paper is in the form of a sermon to her current congregation, illustrated with pithy points from Athanasius.

Now both of them did something that took some intellectual juice. It just wasn’t the intellectual task I assigned — so it didn’t accomplish my course’s goal of helping them think like a historian.

The same problem happens across the curriculum.

Students who had mastered my history papers tried to do that same stroke in theology, and it didn’t work.

They declared a thesis about the past and tried to prove it using sources. But in theology I didn’t want them to prove a point about the past. I wanted them to articulate their views and state a convincing case for them in dialogue with views from the past.

Almost any pair of courses can bring a clash of strokes:

- Do a reflection on your own faith journey in light of a text, when your Bible professor asks for critical exegesis of the passage, and you have a problem.

- Do analytical exegesis when your Pastoral Care professor asks for a reflection on the text in your own faith journey and you have another problem.

Learning to Learn

So the key to seminary is learning to learn. Don’t expect yourself to be perfect in every subject. Step back and try to figure out what skill set the professor is trying to teach, and why — or better still, just ask.

Then, when you know why you are learning what the professor is trying to teach, you have a better chance of coming out with a good and lasting result: a well rounded set of skills for the vocation that lies ahead.

Blessings,

Gary

————

I’d love to hear any stories you are willing to share about learning the various “strokes” or skill sets seminaries set out to teach! Let me know in the comments below.

————

If you liked the post, please share it using one of these handy buttons…

One really helpful “stroke” was preaching.

Rob Hoch always stressed the importance of context — of really knowing a congregation and the larger community and not just writing “in general.”

Nowadays, as I visit people in the congregation or the community I always keep in mind a sermon that I’m working on. Is the sermon really addressing the context? In light of a given conversation, what is God really doing here?

Thanks Gary.

That’s an excellent practice– you are carrying the text in your heart as you encounter the people.

A related or reciprocal one is to always carry the members of your congregation in your heart. Then as you approach the text to prepare for Sunday you have them there and can ask that same question.